Spinal disc herniation

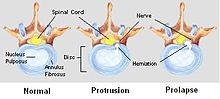

A spinal disc herniation (prolapsus disci intervertebralis) is a medical condition affecting the spine due to trauma, lifting injuries, or idiopathic, in which a tear in the outer, fibrous ring (annulus fibrosus) of an intervertebral disc (discus intervertebralis) allows the soft, central portion (nucleus pulposus) to bulge out beyond the damaged outer rings. Tears are almost always postero-lateral in nature owing to the presence of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the spinal canal. This tear in the disc ring may result in the release of inflammatory chemical mediators which may directly cause severe pain, even in the absence of nerve root compression (see pathophysiology below).

Disc herniations are normally a further development of a previously existing disc "protrusion", a condition in which the outermost layers of the annulus fibrosus are still intact, but can bulge when the disc is under pressure. In contrast to a herniation, none of the nucleus pulposus escapes beyond the outer layers.

Most minor herniations heal within a few weeks. Anti-inflammatory treatments for pain associated with disc herniation, protrusion, bulge, or disc tear are generally effective. Severe herniations may not heal of their own accord and may require surgical intervention.

The condition is widely referred to as a slipped disc, but this term is not medically accurate as the spinal discs are fixed in position between the vertebrae and cannot in fact "slip".

Terminology

Normal situation and spinal disc herniation in cervical vertebrae.

Some of the terms commonly used to describe the condition include herniated disc, prolapsed disc, ruptured disc and slipped disc. Other phenomena that are closely related include disc protrusion, pinched nerves, sciatica, disc disease, disc degeneration, degenerative disc disease, and black disc.

The popular term slipped disc is a misnomer, as the intervertebral discs are tightly sandwiched between two vertebrae to which they are attached, and cannot actually "slip", or even get out of place. The disc is actually grown together with the adjacent vertebrae and can be squeezed, stretched and twisted, all in small degrees. It can also be torn, ripped, herniated, and degenerated, but it cannot "slip".[1] Some authors consider that the term "slipped disc" is harmful, as it leads to an incorrect idea of what has occurred and thus of the likely outcome.[2][3] However, one vertebral body can slip relative to an adjacent vertebral body. This is called spondylolisthesis and can damage the disc between the two vertebrae.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of a herniated disc can vary depending on the location of the herniation and the types of soft tissue that become involved. They can range from little or no pain if the disc is the only tissue injured, to severe and unrelenting neck or low back pain that will radiate into the regions served by affected nerve roots that are irritated or impinged by the herniated material. Often, herniated discs are not diagnosed immediately, as the patients come with undefined pains in the thighs, knees, or feet. Other symptoms may include sensory changes such as numbness, tingling, muscular weakness, paralysis, paresthesia, and affection of reflexes. If the herniated disc is in the lumbar region the patient may also experience sciatica due to irritation of one of the nerve roots of the sciatic nerve. Unlike a pulsating pain or pain that comes and goes, which can be caused by muscle spasm, pain from a herniated disc is usually continuous or at least is continuous in a specific position of the body.

It is possible to have a herniated disc without any pain or noticeable symptoms, depending on its location. If the extruded nucleus pulposus material doesn't press on soft tissues or nerves, it may not cause any symptoms. A small-sample study examining the cervical spine in symptom-free volunteers has found focal disc protrusions in 50% of participants, which shows that a considerable part of the population can have focal herniated discs in their cervical region that do not cause noticeable symptoms.[4][5]

Typically, symptoms are experienced only on one side of the body. If the prolapse is very large and presses on the spinal cord or the cauda equina in the lumbar region, affection of both sides of the body may occur, often with serious consequences. Compression of the cauda equina can cause permanent nerve damage or paralysis. The nerve damage can result in loss of bowel and bladder control as well as sexual dysfunction. See Cauda equina syndrome.

Cause

Disc herniations can result from general wear and tear, such as when performing jobs that require constant sitting. However, herniations often result from jobs that require lifting. Traumatic injury to lumbar discs commonly occurs when lifting while bent at the waist, rather than lifting with the legs while the back is straight. Minor back pain and chronic back tiredness are indicators of general wear and tear that make one susceptible to herniation on the occurrence of a traumatic event, such as bending to pick up a pencil or falling. When the spine is straight, such as in standing or lying down, internal pressure is equalized on all parts of the discs. While sitting or bending to lift, internal pressure on a disc can move from 17 psi (lying down) to over 300 psi (lifting with a rounded back).[citation needed]

Herniation of the contents of the disc into the spinal canal often occurs when the anterior side (stomach side) of the disc is compressed while sitting or bending forward, and the contents (nucleus pulposus) get pressed against the tightly stretched and thinned membrane (annulus fibrosis) on the posterior side (back side) of the disc. The combination of membrane thinning from stretching and increased internal pressure (200 to 300 psi) results in the rupture of the confining membrane. The jelly-like contents of the disc then move into the spinal canal, pressing against the spinal nerves, thus producing intense and usually disabling pain and other symptoms.[citation needed]

There is also a strong genetic component. Mutation in genes coding for proteins involved in the regulation of the extracellular matrix, such as MMP2 and THBS2, has been demonstrated to contribute to lumbar disc herniation.[6]

The majority of spinal disc herniation cases occur in lumbar region (95% in L4-L5 or L5-S1). The second most common site is the cervical region (C5-C6, C6-C7). The thoracic region accounts for only 0.15% to 4.0% of cases.

Cervical

Cervical disc herniations occur in the neck, most often between the fifth & sixth (C5/6) and the sixth and seventh (C6/7) cervical vertebral bodies. Symptoms can affect the back of the skull, the neck, shoulder girdle, scapula,[7] shoulder, arm, and hand. The nerves of the cervical plexus and brachial plexus can be affected.[8]

Thoracic

Thoracic discs are very stable and herniations in this region are quite rare. Herniation of the uppermost thoracic discs can mimic cervical disc herniations, while herniation of the other discs can mimic lumbar herniations.[9]

Lumbar

Lumbar disc herniations occur in the lower back, most often between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebral bodies or between the fifth and the sacrum. Symptoms can affect the lower back, buttocks, thigh, anal/genital region (via the Perineal nerve), and may radiate into the foot and/or toe. The sciatic nerve is the most commonly affected nerve, causing symptoms of sciatica. The femoral nerve can also be affected[10] and cause the patient to experience a numb, tingling feeling throughout one or both legs and even feet or even a burning feeling in the hips and legs.

Example of a herniated disc at the L5-S1 in the lumbar spine.

Pathophysiology

There is now recognition of the importance of “chemical radiculitis” in the generation of back pain.[11] A primary focus of surgery is to remove “pressure” or reduce mechanical compression on a neural element: either the spinal cord, or a nerve root. But it is increasingly recognized that back pain, rather than being solely due to compression, may also be due to chemical inflammation.[11][12][13][14] There is evidence that points to a specific inflammatory mediator of this pain.[15][16] This inflammatory molecule, called tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF), is released not only by the herniated disc, but also in cases of disc tear (annular tear), by facet joints, and in spinal stenosis.[11][17][18][19] In addition to causing pain and inflammation, TNF may also contribute to disc degeneration.[20]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by a practitioner based on the history, symptoms, and physical examination. At some point in the evaluation, tests may be performed to confirm or rule out other causes of symptoms such as spondylolisthesis, degeneration, tumors, metastases and space-occupying lesions, as well as to evaluate the efficacy of potential treatment options.

Physical examination

Main article: Straight leg raise

The Straight leg raise may be positive, as this finding has low specificity; however, it has high sensitivity. Thus the finding of a negative SLR sign is important in helping to "rule out" the possibility of a lower lumbar disc herniation. A variation is to lift the leg while the patient is sitting.[21] However, this reduces the sensitivity of the test.[22]

Imaging

- X-ray: Although traditional plain X-rays are limited in their ability to image soft tissues such as discs, muscles, and nerves, they are still used to confirm or exclude other possibilities such as tumors, infections, fractures, etc. In spite of these limitations, X-ray can still play a relatively inexpensive role in confirming the suspicion of the presence of a herniated disc. If a suspicion is thus strengthened, other methods may be used to provide final confirmation.

- Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan): A diagnostic image created after a computer reads x-rays. It can show the shape and size of the spinal canal, its contents, and the structures around it, including soft tissues. However, visual confirmation of a disc herniation can be difficult with a CT.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A diagnostic test that produces three-dimensional images of body structures using powerful magnets and computer technology. It can show the spinal cord, nerve roots, and surrounding areas, as well as enlargement, degeneration, and tumors. It shows soft tissues even better than CAT scans. An MRI performed with a high magnetic field strength usually provides the most conclusive evidence for diagnosis of a disc herniation. T2-weighted images allow for clear visualization of protruded disc material in the spinal canal.

- Myelogram: An x-ray of the spinal canal following injection of a contrast material into the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid spaces. By revealing displacement of the contrast material, it can show the presence of structures that can cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerves, such as herniated discs, tumors, or bone spurs. Because it involves the injection of foreign substances, MRI scans are now preferred in most patients. Myelograms still provide excellent outlines of space-occupying lesions, especially when combined with CT scanning (CT myelography).

- Electromyogram and Nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS): These tests measure the electrical impulse along nerve roots, peripheral nerves, and muscle tissue. This will indicate whether there is ongoing nerve damage, if the nerves are in a state of healing from a past injury, or whether there is another site of nerve compression. EMG/NCS studies are typically used to pinpoint the sources of nerve dysfunction distal to the spine.

Narrowed space between L5 and S1 vertebrae, indicating probable prolapsed intervertebral disc - a classic picture.

MRI scan of cervical disc herniation between fifth and sixth cervical vertebral bodies. Note that herniation between sixth and seventh cervical vertebral bodies is most common.

MRI scan of cervical disc herniation between sixth and seventh cervical vertebral bodies.

MRI scan of large herniation (on the right) of the disc between the L4-L5 vertebrae.

MRI Scan of lumbar disc herniation between fourth and fifth lumbar vertebral bodies.

Differential diagnosis

- Mechanical pain

- Discogenic pain

- Myofacial pain

- Spondylosis/spondylolisthesis

- Spinal stenosis

- Abscess

- Hematoma

- Discitis/osteomyelitis

- Mass lesion/malignancy

- Myocardial infarction

- Aortic dissection

Treatment

The majority of herniated discs will heal themselves in about six weeks and do not require surgery. One study on sciatica, which can be caused by spinal disc herniation, found that "after 12 weeks, 73% of patients showed reasonable to major improvement without surgery."[23] The study, however, did not determine the number of individuals in the group that had sciatica caused by disc herniation.

Initial treatment usually consists of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory pain medication (NSAIDs), but the long-term use of NSAIDs for patients with persistent back pain is complicated by their possible cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicity.[24] An alternative often employed is the injection of cortisone into the spine adjacent to the suspected pain generator, a technique known as “epidural steroid injection”.[25] Epidural steroid injections "may result in some improvement in radicular lumbosacral pain when assessed between 2 and 6 weeks following the injection, compared to control treatments."[26] In certain settings, however, these injections may result in serious complications.[27]

Ancillary approaches, such as rehabilitation, physical therapy, anti-depressants, and, in particular, graduated exercise programs, may all be useful adjuncts to anti-inflammatory approaches.[24]

Lumbar

Non-surgical methods of treatment are usually attempted first, leaving surgery as a last resort. Pain medications are often prescribed as the first attempt to alleviate the acute pain and allow the patient to begin exercising and stretching. There are a variety of other non-surgical methods used in attempts to relieve the condition after it has occurred, often in combination with pain killers. They are either considered indicated, contraindicated, relatively contraindicated, or inconclusive based on the safety profile of their risk-benefit ratio and on whether they may or may not help:

Indicated

- Patient education on proper body mechanics[28]

- Physical therapy, to address mechanical factors, and may include modalities to temporarily relieve pain (i.e. traction, electrical stimulation, massage)[28]

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)[28]

- Oral steroids (e.g. prednisone or methylprednisolone)[28]

- Epidural cortisone injection[28]

- Intravenous sedation, analgesia-assisted traction therapy (IVSAAT)

- Weight control[28]

- Tobacco cessation

- Lumbosacral back support[28]

- Spinal manipulation: Moderate quality evidence suggests that spinal manipulation is more effective than placebo for the treatment of disk herniation and acute sciatica. [29][30] A 2006 review of published research stated that spinal manipulation is likely to be safe when used by appropriately-trained practitioners,"[31] and research currently suggests that spinal manipulation is safe for the treatment of disk-related pain.[32]

Contraindicated

- Spinal manipulation: According to the WHO, in their guidelines on chiropractic practice, a frank disc herniation accompanied by progressive neurological deficits is a contraindication for manipulation.[33]

Inconclusive

- Non-surgical spinal decompression: A 2007 review of published research on this treatment method found shortcomings in most published studies and concluded that there was only "very limited evidence in the scientific literature to support the effectiveness of non-surgical spinal decompression therapy."[34] Its use and marketing have been very controversial.[35]

Surgical

Surgery is generally considered only as a last resort, or if a patient has a significant neurological deficit.[36] The presence of cauda equina syndrome (in which there is incontinence, weakness and genital numbness) is considered a medical emergency requiring immediate attention and possibly surgical decompression.

Regarding the role of surgery for failed medical therapy in patients without a significant neurological deficit, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that "limited evidence is now available to support some aspects of surgical practice". More recent randomized controlled trials refine indications for surgery as follows:

- The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT)

- Patients studied "intervertebral disk herniation and persistent symptoms despite some nonoperative treatment for at least 6 weeks...radicular pain (below the knee for lower lumbar herniations, into the anterior thigh for upper lumbar herniations) and evidence of nerve-root irritation with a positive nerve-root tension sign (straight leg raise–positive between 30° and 70° or positive femoral tension sign) or a corresponding neurologic deficit (asymmetrical depressed reflex, decreased sensation in a dermatomal distribution, or weakness in a myotomal distribution)

- Conclusions. "Patients in both the surgery and the nonoperative treatment groups improved substantially over a 2-year period. Because of the large numbers of patients who crossed over in both directions, conclusions about the superiority or equivalence of the treatments are not warranted based on the intent-to-treat analysis"[37][38]

- The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group[39]

- Patients studied "had a radiologically confirmed disk herniation...incapacitating lumbosacral radicular syndrome that had lasted for 6 to 12 weeks...Patients presenting with cauda equina syndrome, muscle paralysis, or insufficient strength to move against gravity were excluded."

- Conclusions. "The 1-year outcomes were similar for patients assigned to early surgery and those assigned to conservative treatment with eventual surgery if needed, but the rates of pain relief and of perceived recovery were faster for those assigned to early surgery."

Surgical options

- Chemonucleolysis - dissolves the protruding disc[40]

- IDET (a minimally invasive surgery for disc pain)

- Discectomy/Microdiscectomy - to relieve nerve compression

- Tessys method - a transforaminal endoscopic method to remove herniated discs

- Laminectomy - to relieve spinal stenosis or nerve compression

- Hemilaminectomy - to relieve spinal stenosis or nerve compression

- Lumbar fusion (lumbar fusion is only indicated for recurrent lumbar disc herniations, not primary herniations)

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (for cervical disc herniation)

- Disc arthroplasty (experimental for cases of cervical disc herniation)

- Dynamic stabilization

- Artificial disc replacement, a relatively new form of surgery in the U.S. but has been in use in Europe for decades, primarily used to treat low back pain from a degenerated disc.

- Nucleoplasty[41]

Surgical goals include relief of nerve compression, allowing the nerve to recover, as well as the relief of associated back pain and restoration of normal function.

Complications

Epidemiology

Stages of Spinal Disc Herniation

Disc herniation can occur in any disc in the spine, but the two most common forms are lumbar disc herniation and cervical disc herniation. The former is the most common, causing lower back pain (lumbago) and often leg pain as well, in which case it is commonly referred to as sciatica.

Lumbar disc herniation occurs 15 times more often than cervical (neck) disc herniation, and it is one of the most common causes of lower back pain. The cervical discs are affected 8% of the time and the upper-to-mid-back (thoracic) discs only 1 - 2% of the time.[42]

The following locations have no discs and are therefore exempt from the risk of disc herniation: the upper two cervical intervertebral spaces, the sacrum, and the coccyx.

Most disc herniations occur when a person is in their thirties or forties when the nucleus pulposus is still a gelatin-like substance. With age the nucleus pulposus changes ("dries out") and the risk of herniation is greatly reduced. After age 50 or 60, osteoarthritic degeneration (spondylosis) or spinal stenosis are more likely causes of low back pain or leg pain.

- 4.8% males and 2.5% females older than 35 experience sciatica during their lifetime.

- Of all individuals, 60% to 80% experience back pain during their lifetime.

- In 14%, pain lasts more than 2 weeks.

- Generally, males have a slightly higher incidence than females.